Carl Zeiss Werra: An East German Bauhaus Fantasy Come to Life

Carl Zeiss is a legendary name in photography. Though successful in many other areas related to the field of optics, like in microscopy for instance, it is particularly Zeiss camera lenses that have earned a spot in the pantheon of photographic giants through their engineering excellence and luxurious quality.

Nowhere is that paradoxical situation more jarring than when examining the Carl Zeiss Werra. Arguably one of the company’s most daring, unique, and iconic designs, not to mention a solid seller in its time, it’s at best looked at as a minor curiosity nowadays.

How could this be? And what made the Werra so special, anyway? Strap in and get ready to find out.

The Zeiss That Made the Werra: Carl Zeiss Jena in East Germany After 1945

First of all, it’s important to consider how the history of the Carl Zeiss company factored into the creation, development, and production of the Werra. To understand the history of Carl Zeiss, it turns out that you need to understand the history of Germany, too.

Zeiss did not do much to hide their collaboration with the Nazi regime during the war. As one of the largest optical businesses in the country by the 1930s, it was inevitable that Zeiss would be called upon to assist in the war effort, producing rifle scopes, binoculars, bomb sights, periscopes, and much more. However, what was not part of the Nazi party’s coercion of Zeiss was the company’s widespread adoption of slave labor, much of it sourced from concentration camps.

It was these kinds of crimes that would result in Zeiss being subjected to severe penalties by the war’s end. Following the partition of Germany, Zeiss would exist as a group of separate entities. One Zeiss factory was set up in Stuttgart, with new headquarters in nearby Oberkochen under the American occupation administration. Products made here would be labeled as “ZEISS, West Germany”, or sometimes “Zeiss-Ikon, Stuttgart”, harkening back to the conglomerate founded by, though independent from the main Zeiss business that had been active in the 1920s and 1930s.

The other factory was established in Jena, the place where the Zeiss company had been founded originally. Falling into the Soviet administrative zone, the vast majority of the old infrastructure was removed (little of it had remained due to wartime bombing anyway) and a new factory, staffed by fresh workers, was put in its place. All Zeiss optics and gear made here would be labeled “Zeiss Jena” or “Carl Zeiss Jena”. In addition, a third factory, named VEB Zeiss Ikon, launched in Dresden as a direct counterpart to its Stuttgart-based brother.

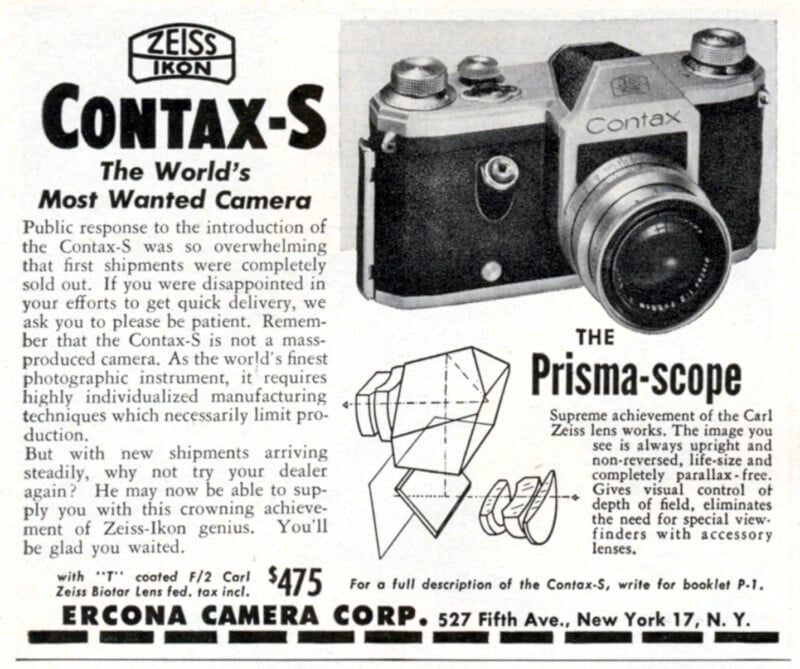

As part of wartime reparations for Zeiss’ collaborative activities, the East German business was further cut up compared to the Western one. For instance, factories on both sides of the Iron Curtain had plans to resume production of the pre-war Contax – a high-end interchangeable-lens rangefinder system that, in the 1930s and 1940s, had been one of the few serious competitors to the Leica.

The West German Zeiss would only make slight changes to the Contax’s specifications, putting it back on sale by 1950. By contrast, the Soviet administration quickly aborted plans to restart East German Contax factory lines in Dresden. Instead, they captured almost all the original tooling left behind from the war and transported it to Kyiv. The Arsenal factory there was the place where almost all of the Soviet Union’s most high-end cameras were made at the time. Under the name Kiev II and III (corresponding to the original Contax model names), Arsenal would keep the pre-war Zeiss design alive for decades to come.

Carl Zeiss Jena, though, would never see any of it, nor would their workers be involved in any way. Management insisted that, in order to survive and especially in order to garner positive attention abroad, Carl Zeiss Jena would have to innovate and produce new, fresh-looking cameras that had no obvious basis in the company’s pre-war designs.

This drive for innovation bore fruit very soon. As early as 1949, VEB Zeiss Ikon presented the Contax S. The name would imply that a Dresden-based Contax reboot had found success after all, but in fact, the camera was all-new – and it wasn’t a rangefinder. Wowing the press with its high-end specs, the Contax S became one of the first interchangeable-lens, pentaprism SLRs to be mass-produced, more than a decade before Japanese brands like Pentax and Nikon entered the fray.

Within a few years, Oberkochen-based Zeiss would also unveil their own debut SLR, the Contaflex – an odd, leaf-shutter camera with a selenium exposure meter that was notorious for its mechanical complexity and brick-like, heavy-bodied build.

And so, the East German Zeiss business established its reputation as a forward-thinking company not afraid to take risks. Meanwhile, Stuttgart-based Zeiss soldiered on as a much more conservative brand more concerned with craftsmanship than bleeding-edge innovation.

A Little Place Named Werra

At some point in the early 1950s, Carl Zeiss Jena received a directive from the East German economic planners to produce a “people’s camera” – simpler, more straightforward to use, and most importantly more affordable than past Zeiss products, without skimping on optical quality.

This came in parallel to a stream of veteran German Zeiss workers who were returning from the Soviet Union’s Arsenal factory around this time and found themselves with comparatively little to do in Jena.

The people’s camera project ended up being rushed over the course of barely a year, the design being finalized by 1954.

The name, curiously enough, came from the small, rural factory where the camera would be produced. Eisfeld, nestled deep in the greenery of Thuringia right by the Werra River, had a population of a few thousand during those early postwar years. Their biggest claim to fame, other than the Werra camera, remains a local razor factory that still produces razor blades for some international brands.

Why exactly the Carl Zeiss Werra was assembled here, and not in the larger factory in Jena or even in Dresden, remains unclear even after all these years.

Unveiling the Werra

Upon its public release in 1954, the Werra stunned both the domestic and international press. In shape and size, the Werra was unmistakably a compact, fixed-lens viewfinder camera with a leaf shutter. In other words, fairly conventional given the time period.

However, there’s no mistaking the Werra for just about any other camera at first glance.

Its body, clad in olive-green leatherette, is one-of-a-kind, imposing and elegant at once. Its silhouette of a beveled rectangular box with only faint embellishments is the peak of minimalism.

The camera’s top plate, usually the place where most essential controls would be found, looks like a void of bare metal. Only a small, convex shutter release button barely protrudes from the top right corner of the Werra, and even that is easy to miss.

Perhaps its most famous and distinctive aesthetic feature, and one of the few that barely changed throughout all of the Werra’s model years, is its unique conical combination lens hood. Matching the olive leatherette covering of the body, the hood screws on in the conventional manner when flipped one way, forming a sunshade. But reverse it, and the hood snaps into a small recess in the Werra’s lens barrel, becoming a protective, shield-like cap. There’s a small, circular screw-on piece provided to additionally protect the front element glass.

It’s often said that the Werra was designed as an ode to pre-war Bauhaus design principles. Judging by its striking industrial design, you couldn’t really fault anyone for thinking that way.

Function And Form

By default, the camera came with a Jena-made Novonar triplet 50mm f/3.5 lens in a Vebur shutter that covered speeds from 1 second to 1/250th, including bulb exposures. For a premium, you could also opt for one of Zeiss’ high-end Tessar f/2.8 lenses instead.

While these components sound fairly straightforward for a compact scale focus camera destined for the bottom end of the Carl Zeiss range circa 1954, it’s the way the camera intends you to interact with its mechanics that’s truly special.

On the Werra’s lens barrel, you’ll find a series of serrated rings. The topmost ring controls the lens aperture, whereas the middle ring sets the focus. Below that, you’ll find a depth-of-field scale and a shutter speed selector, which instead of a ring uses two parallel metal pins that protrude from the lens barrel.

Keep following the lines of the Werra, and you’ll realize there’s another, much larger, knurled ring right at the base where the lens meets the camera’s body. This is part of the Werra’s secret and how its engineers managed to realize its stunning Bauhaus-esque minimalism.

The large knurled ring is multifunctional: by giving it a sharp, counterclockwise turn, the camera winds the film, cocks the shutter, and advances the film counter. Not only did this feature satisfy the “people’s camera” design principle of a device that could be ergonomic and easy to understand and use for the average amateur photographer – it also gave the Werra an immediately recognizable gadget to show off.

All other controls and features, such as the aforementioned film counter along with a rewind knob and a small tripod socket, were located out of sight on the bottom plate of the camera.

Initial Changes

The Werra caught on with its intended customer base fairly quickly, shipping 100,000 units within two years. Quite a respectable performance, given the state of the East German postwar economy! At a rapid pace, Carl Zeiss Jena began introducing revisions to the design – something they would not cease to do until the very end of Werra production.

The very first change was a switch from knurled metal for the combination cocking-winding ring to (what else?) olive green leatherette, in line with the rest of the Werra body. Next, the viewfinder was upgraded by greatly increasing the area of the previously minuscule rectangular eyepiece on the back of the camera and adding projected parallax marks and frame lines.

Finally, the shutter was upgraded to a newer, more high-end Prestor SVS, with a faster 1/500s Synchro-Compur available soon thereafter.

Not all Werras made after 1955 received these upgrades simultaneously, and some only feature odd combinations, making them in-between models. However, the fully upgraded Werras with the new viewfinders, shutters, and olive combination rings would be marketed as the Werra I.

And if you thought that that was a confusing choice, wait till you get to see the subsequent Werras!

Giving the Werra a New Pair of Eyes

A more upscale variant of the Werra I, the Werra II, was released in parallel with its more basic sister model. The major difference between the two was the latter’s inclusion of a built-in exposure meter, a very nice luxury to have in such a compact camera in the mid-1950s.

Of course, being a budget camera, this was an uncoupled meter. To use, you first had to flip open the cover shielding the meter from light when not needed – this was a necessity during the time when selenium-based meters were considered state of the art.

Next, a small scale hidden on the camera’s top plate offered a readout of light values. These light values were then plugged into a rotating scale, not unlike a mechanical calculator, on the back of the camera, which gave you a way of (manually) computing the shutter speed-aperture combination suitable for your exposure.

A very clunky process by today’s standards, then, and one that added a bunch of protrusions to the Werra’s still-elegant body lines – but worth the luxury for many, as the Werra II sold well just the same.

Growing in Complexity

With the Werra III, Carl Zeiss Jena would radically change the camera’s operation to try and appeal to an even broader audience. While successful, the initial series of olive-bodied Werras found some criticism for their limitations. Most importantly, the camera was bemoaned for its basic viewfinder, which, while offering 1:1 magnification, was really hard to see through thanks to the tiny eyepiece. The utility of a scale focus-only camera, even for the budget market, was also becoming more of a dubious proposition as the 1950s neared their close and Japanese SLRs loomed on the horizon.

Sure, the improved, larger viewfinders with projected frame lines that were introduced after the Werra’s initial launch helped somewhat. But Zeiss knew that these small changes alone wouldn’t be enough, so they went ahead and released a major revision of the camera in the form of the Werra III.

Outwardly, not a whole lot changed about this model. The lines of the camera were slightly adjusted, giving it a softer look that felt ever so slightly more snug in the hand. The most immediately noticeable difference is the drastically larger viewfinder window, along with a centrally-located second window for the brand-new, built-in rangefinder. This rangefinder used a prism instead of thin mirrors, making it exceptionally bright, clear, and resistant to fade.

The meter of the Werra II was gone, the space savings restoring much of the original Werra’s minimal appearance. The eyepiece of the viewfinder grew immensely, now forming a circle instead of a rectangle. By means of a small thread, it now also offered diopter adjustment.

But by far the biggest showpiece of the new Werra III was its interchangeable lens mount. That’s right – in addition to the 50mm Tessar, the Werra could now be configured with a 35mm Flektogon f/2.8 as well as a Cardinar 100mm f/4 telephoto. The brand-new prism rangefinder automatically coupled with all these lenses and showed appropriate frame lines for each.

Very impressive is the aesthetic integration of the new mounting mechanism: with a lens mounted, it is indeed very hard to tell whether you’re dealing with a fixed-lens Werra or one of the interchangeable-lens variants such as the III. Unless you know where to look, the small latch that locks and releases the interchangeable lens blends in perfectly with the rest of the camera’s controls.

Along with the Werra III’s release, Carl Zeiss Jena also began offering all the Werra cameras with black leatherette in addition to the original olive green. As time went by and the 1960s entered full swing, the black versions would begin to severely outsell their olive counterpart, making the exterior color a fairly certain – but not foolproof – indicator of a Werra’s age.

Around the same time as the addition of this new colorway, Zeiss also updated their shutter options. The Synchro-Compur, with its 1/500s top speed, remained but became the base choice. A higher-end, modernized version of the Prestor-SVS, called the RVS, took the place of the premium option. This design went up to a breezy 1/750th of a second – very fast indeed for a simple, small leaf shutter!

Cream of the Crop: The Werra IV and Its Successors

Of course, Carl Zeiss Jena couldn’t resist offering a top-of-the-line model combining all of the previous Werras’ features, and so that is what they did with the Werra IV. Essentially a mash-up of the Werra III with the II’s built-in selenium meter, the Werra IV was the most complex model yet.

In the year 1960, this would be followed by the Werra V. Despite the name, this was in fact much more of a revised IV than a completely new model. The biggest difference was twofold: first, another aesthetic revision took place, once again changing the Werra’s silhouette to make it appear ‘softer’ and friendlier to the eye. With chamfered, smooth edges, a curved top plate, and rounded viewfinder windows, it gave the V an even more space-age appearance than the original model.

Unlike the Werra IV and the II before it, the V’s light meter now directly coupled to the camera’s lens, offering much faster metering and exposure. A small needle within the viewfinder directly relayed metering information to the photographer, reducing the need for the top-mounted window and rear calculator of the earlier metered Werras and keeping the camera’s looks intact.

An additional small window displayed in-viewfinder information of currently set aperture and shutter speeds projected by small mirrors – very forward-thinking for the time!

The Werra Goes Automatic

Pretty soon following the V, the Werramat was added to the lineup. This was the first Werra to not be offered in olive green at all. Instead, a plain version with black and silver trim was released first, followed by a complete redesign with a different, more heavily stylized front plate featuring a monochrome stripe pattern and, for the first time, the logo of Carl Zeiss Jena.

This camera, despite following up on the V, was not a direct successor as it actually lacked the coupled rangefinder and the provision for interchangeable lenses. However, the Werramat did contain all of the prior models’ main features, such as the large parallax-corrected viewfinder, coupled light meter, and of course the signature Werra controls, minimalist as ever.

The Final Werra

The very last version of the Carl Zeiss Werra debuted a decade after the original, dubbed the Werramatic. This camera shared the body design of the Werramat (with which it should not be confused, no matter how easy Carl Zeiss Jena made it), but reintroduced the interchangeable lens mount and the coupled rangefinder, becoming the most feature-rich and advanced of all the Werras.

It’s actually hard to tell at first glance, but most of the Werramatics along with the latest versions of the Werramats actually replaced the black leatherette of the earlier models with a same-colored herringbone weave, resulting in a grippier and somewhat sleeker-looking body.

Even after all of these changes, the Werra remained unmistakably a Werra: a vaguely Bauhaus-esque box with a large viewfinder window in the corner, a largely empty top plate with a chromed shutter release button, equipped with a stellar Zeiss lens and the unique matching reversible hood.

The end of Werra production came in the year 1966. The Carl Zeiss Jena business had already been subsumed into the newly-founded, state-run Pentacon conglomerate two years before. The new management decided that Zeiss’ most valuable function was as a lens maker and that scale focus and rangefinder cameras had no economic future in the mid-1960s.

While that’s hard to argue with now in hindsight, the Werra had never stopped being a great seller. By the time production came to a close, Carl Zeiss Jena had put together over 500,000 units!

The Werra’s Legacy

Opinions on the Werra continue to vary. Ever since its initial release, the unique lens-mounted ring advance has been deemed revolutionary by some, frustrating by many others.

And it can be argued that, as a scale focus camera designed right at the precipice of widespread SLR adoption (by one of the companies spearheading SLR development at the time with their own Contax S, no less), the Werra was always going to look like a fashion-forward, mechanically backward piece of kit.

While many aspects of the Werra’s engineering are commendable – including the ingeniously integrated lens mount – others are notorious for their middle-of-the-road quality. This includes especially the bottom-plate controls, which are some of the few aspects of the camera that were never really upgraded during production.

The rewind crank, while fairly standard, has always had a reputation for tearing up rolls of film if the operator isn’t careful enough. Meanwhile, Zeiss somehow chose the least practical design for the film counter, fashioning it with gray-on-gray lettering and impossibly small markings – not to mention putting it on the underside of the camera, to begin with.

Thanks to these kinds of ergonomic flaws and the steady rise in popularity of SLRs and Japanese compact cameras as the Werra’s life went on, it was seen by many as a functionally underwhelming camera that couldn’t count on much more than its radical design.

And speaking of which, that design may have indeed worked against the Werra. Whilst later versions radically improved usability in many ways, it is the original Werra that is the most famous and universally recognized for its distinctive appearance and the impact it made when it first launched.

That is why retrospective reviews of the camera often only include the initial model, ignoring the continuity of later improvements and thus helping to spread the common conception of the Werra as an undercooked disappointment.

Nevertheless, the Werra is undeniably capable of compelling photography. Its optics are a fine example of what Carl Zeiss Jena was capable of during the middle of the century – and versions of the Werra’s Tessar and Flektogon made for other lens mounts still sell for many times the used market value of the camera itself!

The same can be said of the camera’s shutter. Especially the later models with their Prestor-RVS high-speed shutters are well-recognized for solid engineering and high accuracy, even decades after leaving the factory.

While the ergonomics are, as anything as unique as the Werra should be, something to get used to, it deserves to be said that the camera is a high-quality example of craftsmanship from a legendary brand, clad in an iconic industrial design that will remain timeless for years to come.

If anything, that alone should be reason enough to give the Werra a spot in the camera history books.