From Ukraine, With Love: The Perfectly Imperfect Lens

For as long as I’ve been behind the camera, I’ve been the type of person to chase optical perfection. LoCA, coma, and other optical artifacts are to be avoided at all costs.

Recently though, as I have begun accumulating what by most people’s standards is quite a large collection of gear, I’ve found myself seeking out unique and different pieces of equipment, that affect images in a funky, interesting way. I’ve found that vintage lenses are a field ripe for this kind of experimentation.

Perhaps YouTube is just really good at finding exactly the content that’s likely to get me to spend money, or perhaps I’m just particularly vulnerable to being talked (or talking myself) into buying shiny new toys, but a few months ago, I was introduced to Matthieu Stern, a French creator with a particular interest in oddball vintage glass.

After watching a video of his on cleaning and servicing lenses prior to my first foray into tearing down and fixing an old lens I’d gotten for cheap, I was recommended a video buyers’ guide to the Helios 44-2, which at the time I had only heard passing mention of on various analog forum sites. For those of you unfamiliar, as I was, this lens is a 58mm f/2, a Soviet copy of the Zeiss Biotar lens formula that essentially became a kit lens with many inexpensive cameras manufactured in the USSR.

I don’t really know what drove me to watch. I guess I can chalk it up to Matthieu just being a quite good host that draws viewers into a rabbit hole from which there is no escape, but I was fascinated by the sample images, having never seen or even properly heard of the lens before. I quickly resolved to look for a nice copy, as I was eager to add such a unique color to my creative palette.

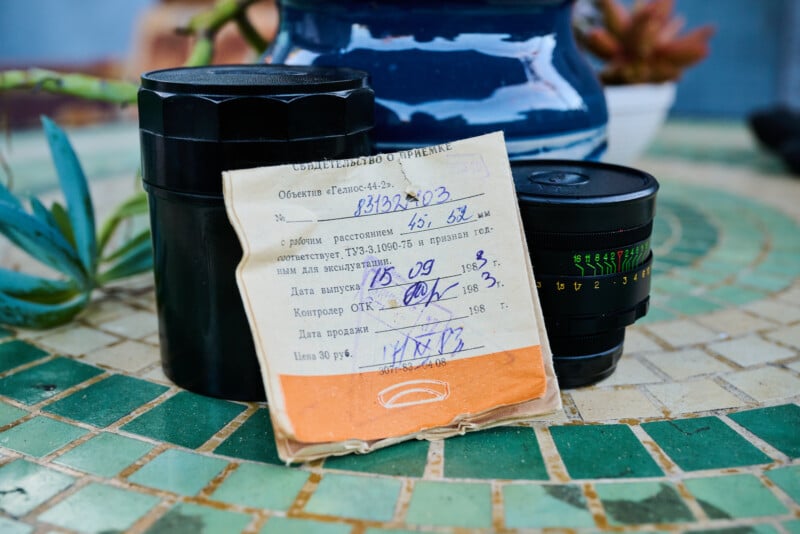

After a short while, I came across what seemed to be exactly what I was looking for. Readers of my previous work will know by now that I’m a sucker for beautiful examples of gear that really shouldn’t be in such good shape given their age, and eBay user UkraineShopStudio had for sale what can only be described as a time capsule copy. Not only was the lens itself free of any visible wear or marks of any kind, but included with it were both its original end caps, screw-top case, and even its original manufacturing slip with handwritten notes from the factory. It was as if it had never been used. Sold.

Once it arrived a few weeks later, I was itching to mount it up and do some shooting, which required the purchase of the requisite adapters to marry the M42 lens mount to my vintage Minoltas and my daily Nikon Z9. For the time being, most of my shooting has been on the latter since I would prefer to get to grips with using the lens while taking advantage of all of the benefits a digital platform provides before I begin burning frames trying to get shots on film.

The first thing I think I should say is that this lens is of a focal length and aperture that are admittedly a little awkward for me to use. 58mm is slightly longer than you’d really want for a general-purpose walkaround lens, and slightly shorter than what most people would consider the traditional “portrait” lens of about 85mm.

Aside from that, I really am not used to a lens of this length with a maximum aperture of only f/2, especially given that the aperture mechanism in this lens took some serious work to get used to. Rather than a simple clicked or clickless ring at the rear, the Helios uses two rings at the very front. It’s called a “preset” aperture system, and can best be described thusly: one ring sets the minimum aperture (with the highest f-number), while the other actuates the blades. The thinking is that one can “preset” the desired aperture value for the photo, compose the shot with the diaphragm wide open, and then quickly close it down to the desired value just before shooting. Potentially useful, but personally I’m not really sold on it.

Secondly, this lens is explicitly not sharp. It’s not just mine, either, since I’ve heard and seen similar results from colleagues who also own copies. Center sharpness is decent for being such an old and cheap bit of kit, but on the edges, you’re going to notice very soft detail and mountains of coma. In fairness, I might’ve been asking a lot of it by mounting it to a high-resolution flagship body, and it might have fared better on something like a Nikon Z6 III or when shooting on film with a very high-speed roll (especially given that plenty of movies have been shot on this lens), but it’s safe to say that pixel-peepers such as myself will probably not have anything to write home about.

Flaring is severe, as well. I’m not sure whether this is due to the optical design, a lack of modern coatings, or something else, but if you so much as suggest that you might want to shoot with a bright light in the frame, you’ll quickly see huge, bright flares taking up much of the frame.

Happily, however, this is an effect that, unlike soft focus or smudgy points of light, I happen to really enjoy when it’s applied in a way that helps add intrigue to the image. I’m very much a fan of the crazy J. J. Abrams lens flare, as many of my friends and colleagues will tell you with a roll of their eyes.

Of course, the thing that everyone talks about with this lens is the swirly bokeh, a side effect of the optical design that essentially results in a very strong cat’s-eye bokeh effect, that propagates in a circular, vignette-like pattern when the focal plane is significantly different to the plane occupied by light sources. You can see some of that in the above photo in the trees, but I knew there had to be more to get out of it.

And boy howdy, was there. While visiting the amazing Griffith Observatory, I met a tourist couple who agreed to let me take their picture, and I was gobsmacked at the result. Sure, it may not have the clinical sharpness of something like a 135mm Plena, and I really missed having image stabilization available to let me get away with a slower shutter speed, but I’ve never seen such a unique rendering of bokeh.

This is where I think this lens truly shines. It may be slightly shorter than what we might consider a “portrait” lens, but it’s absolutely fantastic in that role, simply because its unique bokeh characteristics synergize so well with what is typically desirable in that application.

In using the Helios 44-2, I’m happy to report that I’ve begun to understand what other photographers really mean when they say that they love the “character”, “rendering”, or other relatively-nebulous terms used to describe the images a particular piece of gear creates. For the longest time, I sought absolute, uncompromising perfection in all of my work, poring over every single detail to deliver the sharpest, most ideal version of my product every time. What I now realize I was failing to appreciate is that photography is as much an art as it is the science I was treating it to be.

As an artist, it’s all well and good to aspire to some idealized vision of what I seek to create, but I should be more open to taking liberties in that department if they deliver an end result that might very well be more engaging.

Long story short, lighten up, and experiment. You might be surprised by what comes of doing so.

Author’s note (added on 4/22/25): To address some of the reader comments concerning the country of origin of this lens, I am aware that this particular lens was produced at the BelOMO plant in Belarus. The ‘From Ukraine’ bit of the title was merely referencing the fact that this copy ended up with, and was purchased from, a seller in Ukraine, not that the lens itself is of Ukrainian design or manufacture.