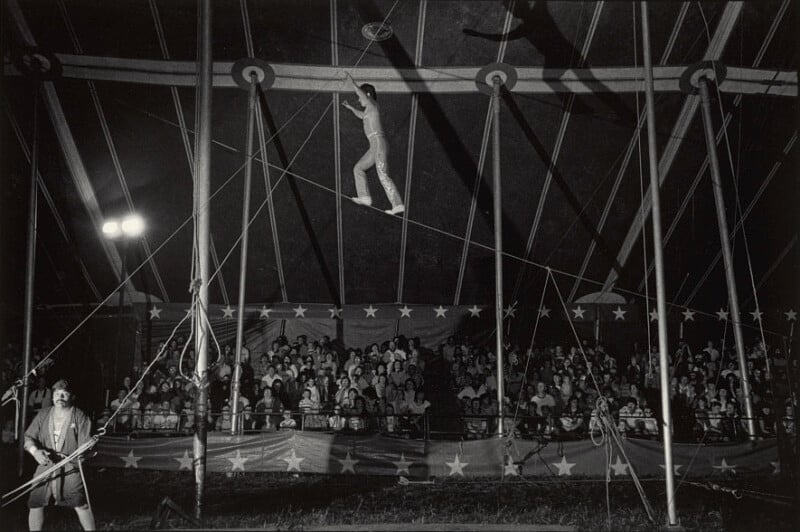

Photographer’s Stark Images of Circus Life in the 1980s

The Library of Congress looks after some of the nation’s most important images and it recently acquired a fascinating set of photos taken by Edwin Martin who documented six traveling circuses from 1983 to 1986.

Martin donated 138 of his circus photographs and the Library of Congress recently published seven of them in a blog post alongside an interview with the photographer for World Circus Day (April 19).

Martin’s journey photographing the circus started in 1983, almost by accident when he was a philosophy professor at Indiana University Bloomington and beginning to explore photography. He started snapping pictures of his sons on a Pentax K1000 and later enrolled in a photo course at the university.

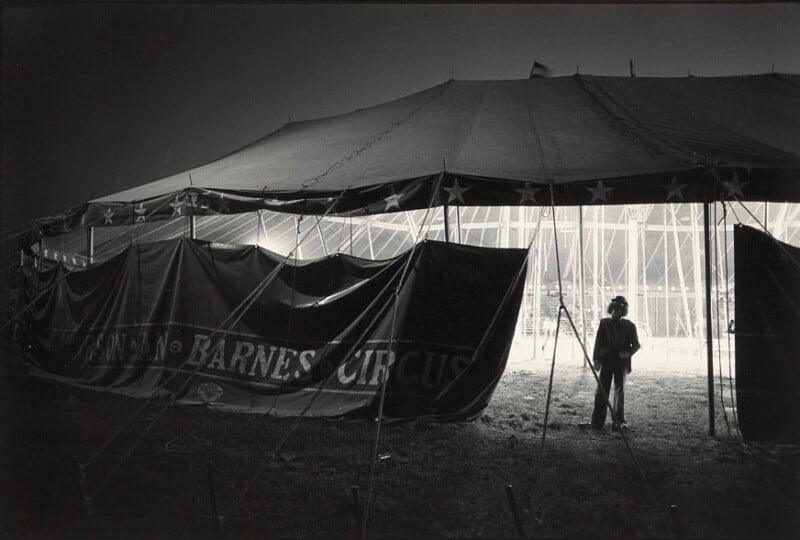

One afternoon in 1983, he photographed the Carson & Barnes Circus during a stop in Indiana. He liked one of the pictures enough to send it to the company, along with a bold offer: allow him to join the circus on the road, camera in tow. To his surprise, they said yes.

By the spring of 1984, Martin found himself in Lake Isabella, California, where the circus was raising its tent in the desert heat. He captured an ethereal photo of light pouring through the holes in the canvas, catching the afternoon light. “It was very dusty and very dirty,” he tells the Library of Congress.

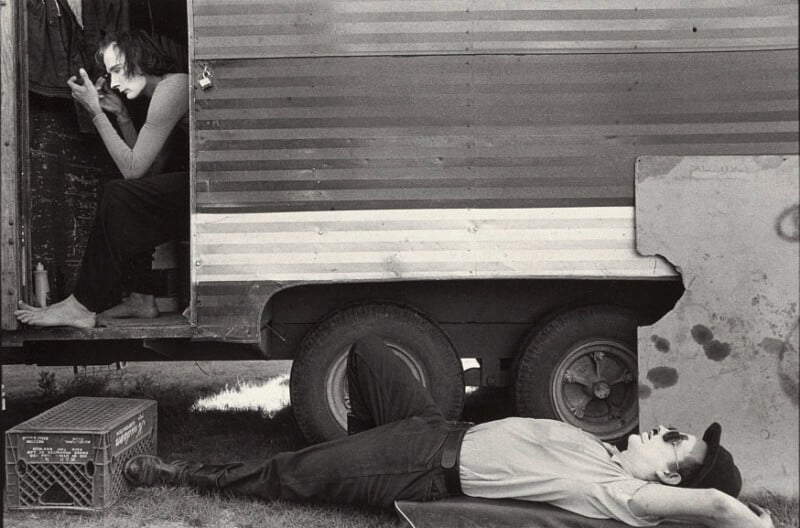

Over the next three weeks, Martin traveled with Carson & Barnes across six states. “We got up before dawn,” he says. “We got in the trucks and drove for 100 miles.” On arrival, performers and workers piled out to unload the animals and unroll the tent. Martin documented it all: the unguarded moments of fatigue, the fragments of daily life, the hard physical work behind the spectacle.

One photo from Dalhart, Texas stands out to him. It shows a clown named Phil applying his makeup while another, EJ, sleeps nearby. “It illustrates the need to sleep whenever you can,” Martin says. The image shows the fractured rhythm of circus life, where days begin early and end late.

Traveling without a mobile darkroom, Martin had to wait for his photos to be developed before he could take a look at what he was capturing. He explains that one shot he was trying to get was EJ the clown silhouetted by the night inside a tent. Nowadays, photographers just look at their LCD screen to check if the exposure is correct. But on film, you’re flying in the dark.

But when he reconnected with Carson & Barnes in Wisconsin the following year, Martin brought prints to hand out. “They enjoyed having the pictures,” he tells the Library. “There were a lot of people taking pictures of them, but not a lot of people giving pictures to them.”

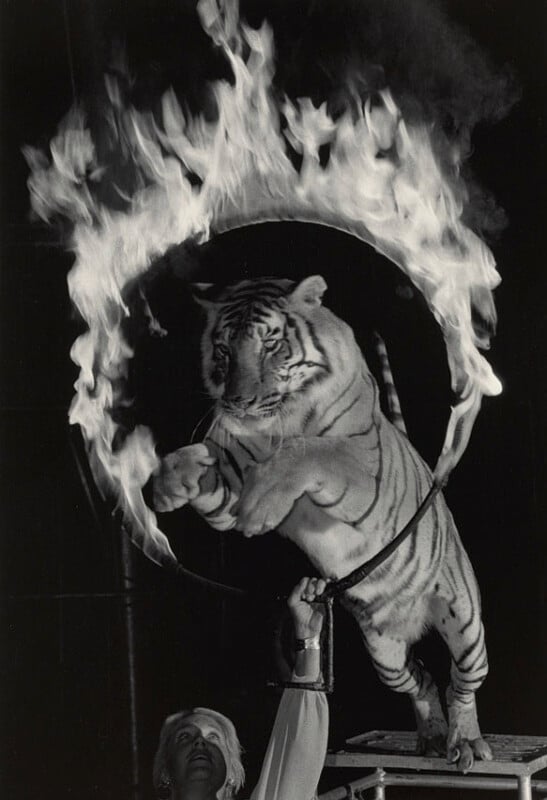

The project left Martin with lasting respect for the performers. He remembers the highwire acts enduring sweltering temperatures at the top of the tent and the quiet skill of Pat, a big cat trainer. “She was skilled and had special knowledge,” he says. “She was a valued member of the troupe.”

The article doesn’t mention the controversy of keeping animals in the circus, something that repels a lot of people and is banned in a handful of states. In 2017, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus permanently stopped using animals after a 146-year run.

Nevertheless, the circus project helped shape Martin’s path as a photographer. After the series ended in 1986, he continued shooting, including assignments for The Indianapolis News and personal projects on rural life.

Looking back, he says, “I think one of the strengths of photography… is documenting ways of life that we don’t really know, that we only have vague ideas about.”

Image credits: Photographs by Edwin Martin/The Library of Congress