Wildlife Filmmaker Explains What It’s Like Filming Penguins in -50° Weather

National Geographic‘s new three-part documentary, Secrets of the Penguins, premiered last Sunday and enchanted viewers with, as its name suggests, incredible footage of penguins. The series, produced by James Cameron and led by Nat Geo Explorer and award-winning filmmaker Bertie Gregory required an incredible 274 days of filming in extreme environments. The three-person overwintering crew included wildlife filmmaker Helen Hobin, who spoke with PetaPixel about the experience.

Hobin, a BAFTA-nominated wildlife cinematographer, specializes in long-lens behavioral shots and immersive drone sequences. While no stranger to working in frigid environments — Hobin worked on the acclaimed Frozen Planet II for BBC from 2019 to 2022 — her work on Secrets of the Penguins took things to the extreme.

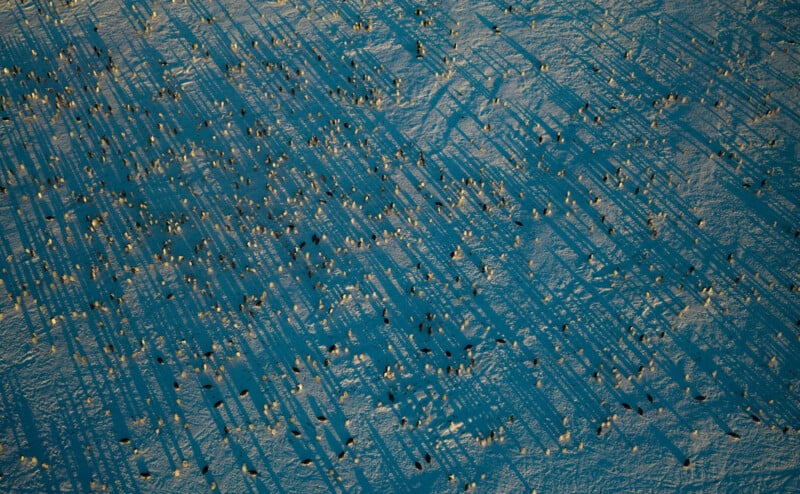

She lived and worked in Antarctica from February to November last year. During the nine months there, she worked on sea ice in temperatures down to -50 degrees Fahrenheit (-45 degrees Celsius). Through two months of the polar night, remember, the summer months in the northern hemisphere are the dead of winter in Antarctica; Hobin witnessed the incredible ways penguins survive and thrive in one of the harshest winters on Earth.

“Overwintering in Antarctica to film emperor penguins is unlike any shoot I’ve done before,” Hobin tells PetaPixel. “Normally you have perhaps three or four weeks on a wildlife shoot, whereas this was a nine-month long expedition. It was extraordinary to have such a long period in one place, with one species, but despite that we still felt the immense pressure of time challenges.”

The hardships were well worth it, as many vital emperor penguin behaviors the crew wanted to see only last for a few weeks, such as courtship and egg hatching.

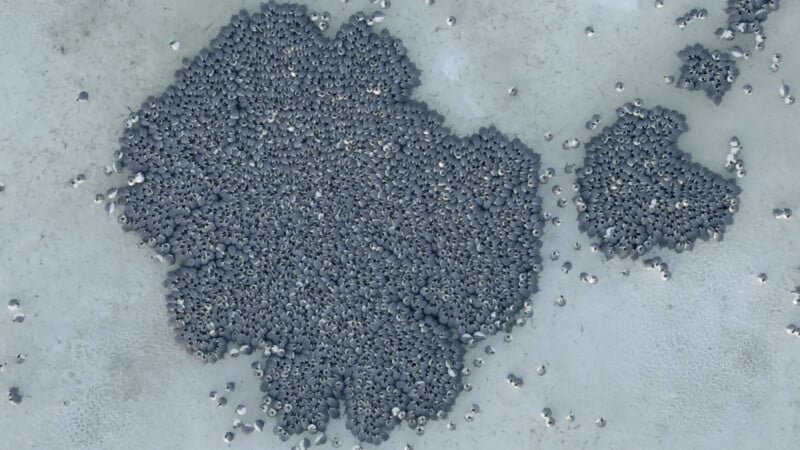

The team was stationed at Neumayer III, AWI’s remote German station in Atka Bay. Once they arrived in February, they knew that was it — there would be no flights in or out during the winter. For most of the nine months there, only a dozen people were at the base. And 20,000 penguins.

Being present in Antarctica is only one aspect of getting the required shots. The team is at the mercy of the weather.

“Where and how we could film was dictated by conditions like when the sea ice would safely freeze over and how long a storm would last. In September howling winds raged for two weeks straight, shaking the station and preventing us from opening the ramp to the station garage, where our snowmobiles were stored. Even if we had been able to navigate to the colony (impossible in a white-out!) the wind would have ripped the windscreens from the skidoos and filled the camera lenses with snow in a matter of moments. When that storm finally eased, we got a single filming day before the next one set in.”

In addition to the team being unable to leave Antarctica during the winter, they could not receive deliveries. If any gear broke and required parts to fix, they were out of luck.

“We put a lot of time and effort into kit prep,” Hobin explains. The team worked with gear rental company Films@59, tested the rigs ahead of time in a -50 degree freezer, commissioned custom camera polar covers from Kirsten Custom Bags, and got special laser-cut inserts for Pelican cases. AWI also provided overwinter training to prepare the team for the expedition.

“Our little filming team comprised three people: Pete McCowen as Director of Photography, Alex Ponniah as Field Producer and myself as Cinematographer. We joined a team of 9 Germans who were working in the traditional Overwintering roles, including station leader/doctor, chef, engineers and scientists. We undertook months of training, which taught us vital skills whilst providing a test-run for working together in stressful situations. We learned how to rescue each other from crevasses, how to make an emergency camp if lost in a storm and, vitally, how to fight fires. It might sound odd when your new home is surrounded by snow, but fire is one of the biggest risks — if the station burns down, there aren’t many options for shelter!” Additional film crews worked in Antarctica at other times but did not overwinter there.

Hobin, McCowen, and Ponniah were sent out by the production company Talesmith, who Hobin says was highly supportive. Talesmith provided a spare kit, including replacement drones and a back-up Canon CN20.

“We hoped to never open those boxes, but Antarctica had different ideas!” Hobin says.

Talesmith also sent the team to Svalbard, Norway for sea ice safety training.

“On location during one filming day the temperature dropped down to -46.8 degrees C absolute, -58.6 degrees C with windchill. Our hands would start to feel like claws, and often our eyes would try to freeze shut, or even freeze open. The monitors and EVFs would ‘ghost’, showing us three versions of every penguin, and batteries would give up and cut out without warning. Even driving to work could be challenging. A 45-minute snowmobile journey was made longer when navigating over sastrugi — ice ridges formed by the wind,” the filmmaker says.

However, despite the challenges, Hobin “loved working in the intense cold.”

“There’s something wild and beautiful in the extremity. I consider myself extremely lucky to have had the opportunity to Overwinter, and I’d go back to Antarctica in a heartbeat.”

The Gear That Survived the Antarctic Winter (and Curious Penguins)

As Hobin says, new nature documentaries typically leverage the latest and greatest camera equipment. However, for overwintering in Antarctica, the priority was reliability, not novelty.

“Often new wildlife series focus on the latest gadgets and fiddly electronic tech, which can be brilliant, but in such extreme conditions we needed to pour our efforts into bolstering our core camera tools — and keeping them alive!” Hobin explains.

She and the team used RED V-Raptors as their main cameras because of “their excellent dynamic range and ruggedness,” alongside Canon CN20 lenses.

When shooting in very low light, the team also used Sony FX6 cameras thanks to their low-light capabilities. They even used the FX6 to film auroras in real time — not a timelapse.

“We fixed dovetail plates to the top and bottom of the rigs so that we could swap between having them top-mounted on a tripod and underslung, without needing to adjust any accessories in the freezing cold. Keeping batteries warm was essential, and we worked with Films@59 to create heating systems inside our polar covers.”

Bristol-based engineer Chris Evans built a special snow-ready “quad pod” for Hobin to use, ensuring she could get her camera extremely low to the ground to film the tiny penguin chicks.

“It was a lightweight aluminum rig on snowboards, so I was able to slide it over the ice to reposition while keeping my long-lens underslung.”

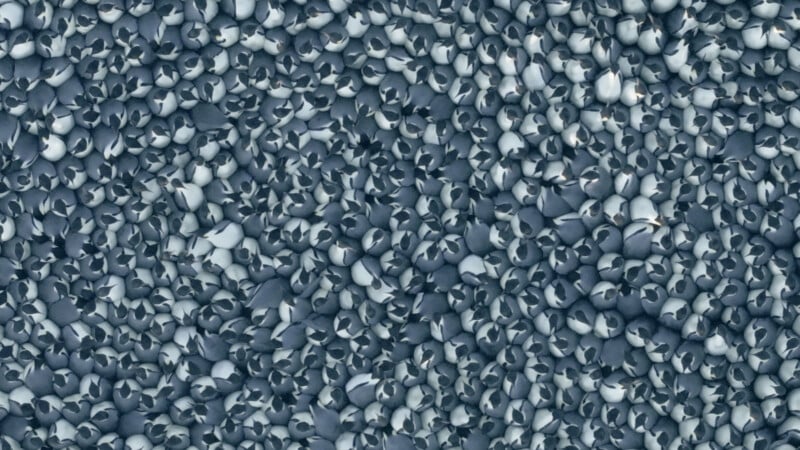

While it is reasonable to suspect that the elements were the greatest filming challenge Hobin and others faced, the more significant hurdle was much cuter: curious penguins!

“Just when we were capturing a pivotal moment like the hatching of an egg, another adult (or twenty!) would plonk themselves in front of the lens. Being able to slide our cameras to the side really helped.”

For drones, Hobin used DJI Inspire 3 and Mavic 3 Cine Pro units. Since they needed to use touchscreens on the controllers, which are very hard to use in subzero temperatures, they used styluses instead of fingers.

“Our hands would go numb instantly if we removed our gloves,” Hobin says.

Hobin’s Path to Antarctica

Helen Hobin took a “somewhat unusual route” into wildlife filmmaking. She has always loved storytelling and studied English Literature at university. But after getting involved with student television while at school, she began traveling to London to work as a “runner,” assisting camera crews on her days off from school.

“As soon as I decided to work in television, my aim was wildlife documentaries,” Hobin says. “I’ve loved the natural world for as long as I can remember.”

“But despite there already being some brilliant female role models — Sophie Darlington and Justine Evans for example — at that point it hadn’t fully occurred to me that camerawomen existed, and that I could be one. I assumed I would need to be a producer.”

“When I was asking a cameraman in London how I could better help him, he asked if I was planning to go into camerawork. It was a lightbulb moment for me. I took a job as a kit technician at facilities house HotCam and spent three years learning everything I could about prepping, fixing and using a whole range of camera, lighting and sound equipment. After building up a wildlife showreel from endless hours spent practicing in the UK and investing in skills like scuba diving, rope access and driving a powerboat, I got a position at the BBC Natural History Unit, working on Frozen Planet II.”

As expected, Hobin learned a lot during Frozen Planet II, working alongside world-class cinematographers and producers.

She started by doing assistance and timelapse rigging, setting up camera traps, and doing long-lens behavioral filming from hides. She shot some of the series’s drone sequences as well.

“From there I got a position as BBC Camera Bursary on the new NBC series The Americas and was lucky to be out on back-to-back shoots. Whilst I was filming for them in Canada, I got a message from Talesmith, and we started talking about a very surreal concept — a shoot to film emperor penguins for National Geographic,” Hobin recalls.

Hobin Has Filmed So Many Animals

“I’ve been fortunate to film quite a wide variety of animals so far. Every shoot is so different, and the learning involved is addictive. Filming birds for example has given me the opportunities to live on a remote island studying the Antipodean wandering albatross; to work from a swaying tree platform 30 meters up in the rainforest capturing harpy eagle footage; to operate in camouflage from grasslands watching sharp-tailed grouse dance, and now to spend an Antarctic winter witnessing the endurance of emperor penguins,” Hobin says.

She has also filmed finicky felines, including the “grumpy” looking Pallas’s cats in Mongolia and Amur tigers.

“One day I would love to film any species of wolf. Going back to my literature roots, I’m keen to help dispel the ‘big bad wolf’ mythology,” Hobin says.

But What About the Penguins?

Every species has something incredible to offer filmmakers like Hobin and viewers at home. Every animal is interesting, dynamic, and engaging.

During filming for Secrets of the Penguins, Hobin filmed many incredible moments, but a few stand out.

“The sea ice froze very late for us. I believe it was the latest it had happened for at least 12 years. By the time we got safely down onto the ice with the colony we had limited light left. We entered the polar night — two months during which the sun doesn’t breach the horizon. After watching these incredible penguins endure the darkness and so many fierce storms it was incredibly rewarding to feel the rays of sunshine return as their eggs began to hatch. Tiny beaks poking out of eggshells. Getting to film such a special moment with the emperors backlit amid gently drifting snow was magical,” Hobin says.

Another “incredibly surreal moment” was when watching the aurora Australis, “southern lights,” dancing across the sky while the huddling male emperor penguins, bathed in colorful light, protected their eggs.

“The night sky in Antarctica is unparalleled,” Hobin says.

A significant part of getting the perfect shots is working closely with scientists, who Hobin says are “absolutely key to wildlife filmmaking.”

“It is one of the greatest privileges of the job to collaborate with leading experts, and to learn from them in the field. As cinematographers we’re lucky to often spend 12-14 hours a day getting to observe the animals we’re filming. To just sit and watch, through the lens, as we film,” Hobin explains.

“Biologists have so much important work to do that they don’t always have that gift of time. And because we’re recording, we get to give back by showing them new and unexpected behaviors sifted from hundreds of hours of observation. And hopefully through documentaries to help play some small part in their conservation efforts.”

As only the fourth or fifth film crew to ever overwinter in Antarctica to film emperor penguins, Hobin, McCowen, and Ponniah observed some incredible things.

“On one day, I filmed an adult couple taking it in turns to pass a block of ice, carefully placing it on their feet with their beaks. It seemed like the same techniques used to swap eggs and chicks over between parents — perhaps they were practicing!” Hobin says.

The team regularly sent proxy footage back to Talesmith and James Cameron for updates and reviews. However, communication with the outside world was generally limited.

“Our expedition felt reminiscent of going to space, or to the depths of the ocean, and it was fascinating to discuss the isolation and the feel of that experience with him.”

More Secrets of the Penguins

Secrets of the Penguins is available now as a three-part documentary. The episodes are streaming now on Disney+ and Hulu. The show was produced by Talesmith for National Geographic and is executive produced by James Cameron and Maria Wilhelm. Bertie Gregory is the lead storyteller, and the series relies upon the work of more than 70 wildlife filmmakers like Helen Hobin and accomplished biologists and other scientists.

People can stay up to date with Helen Hobin as she embarks on her next adventures on Instagram and her website.

Image credits: National Geographic